|

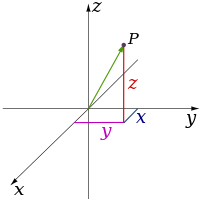

| Cartesian (3-dimensional) |

|

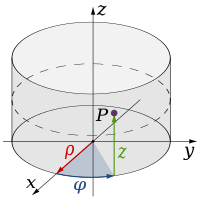

| Latitude and longitude |

Spatial dimensions

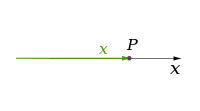

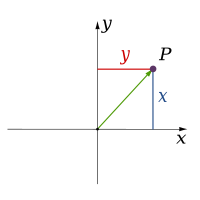

Classical physics theories describe three physical dimensions: from a particular point in space, the basic

directions in which we can move are up/down, left/right, and forward/backward. Movement in any other

direction can be expressed in terms of just these three. Moving down is the same as moving up a negative distance. Moving diagonally upward and forward is just as the name of the direction implies; i.e.,

moving in a linear combination of up and forward. In its simplest form: a line describes one dimension, a plane describes two dimensions, and a cube describes three dimensions. |

| Number line |

|

| Cartesian (2-dimensional) |

|

| Cylindrical |

Time

A temporal dimension is a dimension of time. Time is often referred to as the "fourth dimension" for this reason, but that is not to imply that it is a spatial dimension. A temporal dimension is one way to measure physical change. It is perceived differently from the three spatial dimensions in that there is only one of it, and that we cannot move freely in time but subjectively move in one direction.

The equations used in physics to model reality do not treat time in the same way that humans commonly perceive it. The equations of classical mechanics are symmetric with respect to time, and equations of quantum mechanics are typically symmetric if both time and other quantities (such as charge and parity) are reversed. In these models, the perception of time flowing in one direction is an artifact of the laws of thermodynamics (we perceive time as flowing in the direction of increasing entropy).

The best-known treatment of time as a dimension is Poincaré and Einstein's special relativity (and extended to general relativity), which treats perceived space and time as components of a four-dimensional manifold, known as spacetime, and in the special, flat case as Minkowski space.

A temporal dimension is a dimension of time. Time is often referred to as the "fourth dimension" for this reason, but that is not to imply that it is a spatial dimension. A temporal dimension is one way to measure physical change. It is perceived differently from the three spatial dimensions in that there is only one of it, and that we cannot move freely in time but subjectively move in one direction.

The equations used in physics to model reality do not treat time in the same way that humans commonly perceive it. The equations of classical mechanics are symmetric with respect to time, and equations of quantum mechanics are typically symmetric if both time and other quantities (such as charge and parity) are reversed. In these models, the perception of time flowing in one direction is an artifact of the laws of thermodynamics (we perceive time as flowing in the direction of increasing entropy).

The best-known treatment of time as a dimension is Poincaré and Einstein's special relativity (and extended to general relativity), which treats perceived space and time as components of a four-dimensional manifold, known as spacetime, and in the special, flat case as Minkowski space.

Additional dimensions

In physics, three dimensions of space and one of time is the accepted norm. However, there are theories that attempt to unify the fundamental forces by introducing more dimensions. Superstring theory, M-theory and Bosonic string theory respectively posit that physical space has 10, 11 and 26 dimensions, respectively. These extra dimensions are said to be spatial. However, we perceive only three spatial dimensions and, to date, no experimental or observational evidence is available to confirm the existence of these extra dimensions. A possible explanation that has been suggested is that space acts as if it were "curled up" in the extra dimensions on a subatomic scale, possibly at the quark/string level of scale or below.

An analysis of results from the Large Hadron Collider in December 2010 severely constrains theories with large extra dimensions.

Other physical theories that have introduced extra dimensions of space are:

Kaluza–Klein theory introduces extra dimensions to explain the fundamental forces other than gravity (originally only electromagnetism).

Large extra dimension and the Randall–Sundrum model attempt to explain the weakness of gravity. This is also a feature of brane cosmology.

Universal extra dimension

In physics, three dimensions of space and one of time is the accepted norm. However, there are theories that attempt to unify the fundamental forces by introducing more dimensions. Superstring theory, M-theory and Bosonic string theory respectively posit that physical space has 10, 11 and 26 dimensions, respectively. These extra dimensions are said to be spatial. However, we perceive only three spatial dimensions and, to date, no experimental or observational evidence is available to confirm the existence of these extra dimensions. A possible explanation that has been suggested is that space acts as if it were "curled up" in the extra dimensions on a subatomic scale, possibly at the quark/string level of scale or below.

An analysis of results from the Large Hadron Collider in December 2010 severely constrains theories with large extra dimensions.

Other physical theories that have introduced extra dimensions of space are:

Kaluza–Klein theory introduces extra dimensions to explain the fundamental forces other than gravity (originally only electromagnetism).

Large extra dimension and the Randall–Sundrum model attempt to explain the weakness of gravity. This is also a feature of brane cosmology.

Universal extra dimension

Networks and dimension

Some complex networks are characterized by fractal dimensions. The concept of dimension can be generalized to include networks embedded in space. The dimension characterize their spatial constraints.

Perhaps the most basic way the word dimension is used in literature is as a hyperbolic synonym for feature, attribute, aspect, or magnitude. Frequently the hyperbole is quite literal as in he's so 2-dimensional, meaning that one can see at a glance what he is. This contrasts with 3-dimensional objects, which have an interior that is hidden from view, and a back that can only be seen with further examination.

Science fiction texts often mention the concept of dimension, when really referring to parallel universes, alternate universes, or other planes of existence. This usage is derived from the idea that to travel to parallel/alternate universes/planes of existence one must travel in a direction/dimension besides the standard ones. In effect, the other universes/planes are just a small distance away from our own, but the distance is in a fourth (or higher) spatial (or non-spatial) dimension, not the standard ones.

One of the most heralded science fiction novellas regarding true geometric dimensionality, and often recommended as a starting point for those just starting to investigate such matters, is the 1884 novel Flatland by Edwin A. Abbott. Isaac Asimov, in his foreword to the Signet Classics 1984 edition, described Flatland as "The best introduction one can find into the manner of perceiving dimensions."

The idea of other dimensions was incorporated into many early science fiction stories, appearing prominently, for example, in Miles J. Breuer's The Appendix and the Spectacles (1928) and Murray Leinster's The Fifth-Dimension Catapult (1931); and appeared irregularly in science fiction by the 1940s. Classic stories involving other dimensions include Robert A. Heinlein's —And He Built a Crooked House (1941), in which a California architect designs a house based on a three-dimensional projection of a tesseract, and Alan E. Nourse's Tiger by the Tail and The Universe Between (both 1951). Another reference is Madeleine L'Engle's novel A Wrinkle In Time (1962), which uses the 5th dimension as a way for "tesseracting the universe" or in a better sense, "folding" space to move across it quickly. The fourth and fifth dimensions were also a key component of the book The Boy Who Reversed Himself, by William Sleator.

Philosophy

In 1783, Kant wrote: "That everywhere space (which is not itself the boundary of another space) has three dimensions and that space in general cannot have more dimensions is based on the proposition that not more than three lines can intersect at right angles in one point. This proposition cannot at all be shown from concepts, but rests immediately on intuition and indeed on pure intuition a priori because it is apodictically (demonstrably) certain."

Space has Four Dimensions, is a short story published in 1846 by German philosopher and experimental psychologist Gustav Fechner (under the pseudonym Dr. Mises). The protagonist in the tale is a shadow who is aware of, and able to communicate with, other shadows; but is trapped on a two-dimensional surface. According to Fechner, the shadow-man would conceive of the third dimension as being one of time. The story bears a strong similarity to the "Allegory of the Cave", presented in Plato's The Republic written around 380 B.C.

Simon Newcomb wrote an article for the Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society in 1898 entitled "The Philosophy of Hyperspace".Linda Dalrymple Henderson coined the term Hyperspace philosophy in her 1983 thesis about the fourth dimension in early-twentieth-century art. It is used to describe those writers that use higher-dimensions for metaphysical and philosophical exploration. Charles Howard Hinton (who was the first to use the word "tesseract" in 1888) and Russian esotericist P. D. Ouspensky are examples of "hyperspace philosophers".

In 1783, Kant wrote: "That everywhere space (which is not itself the boundary of another space) has three dimensions and that space in general cannot have more dimensions is based on the proposition that not more than three lines can intersect at right angles in one point. This proposition cannot at all be shown from concepts, but rests immediately on intuition and indeed on pure intuition a priori because it is apodictically (demonstrably) certain."

Space has Four Dimensions, is a short story published in 1846 by German philosopher and experimental psychologist Gustav Fechner (under the pseudonym Dr. Mises). The protagonist in the tale is a shadow who is aware of, and able to communicate with, other shadows; but is trapped on a two-dimensional surface. According to Fechner, the shadow-man would conceive of the third dimension as being one of time. The story bears a strong similarity to the "Allegory of the Cave", presented in Plato's The Republic written around 380 B.C.

Simon Newcomb wrote an article for the Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society in 1898 entitled "The Philosophy of Hyperspace".Linda Dalrymple Henderson coined the term Hyperspace philosophy in her 1983 thesis about the fourth dimension in early-twentieth-century art. It is used to describe those writers that use higher-dimensions for metaphysical and philosophical exploration. Charles Howard Hinton (who was the first to use the word "tesseract" in 1888) and Russian esotericist P. D. Ouspensky are examples of "hyperspace philosophers".

No comments:

Post a Comment